October 28

It’s early morning. There was snow in the night, our first snow of the winter, and it covers the long green grass and deep layer of maple leaves on our lawn. We are not prepared for this snow, have not done the fall chores required to live in a frozen state for the next six months. I’m looking out the window and thinking: these leaves be raked, the water lines down to the sheep fields must be drained, the greenhouse buttoned down… Most of all, the barn foundation is half-way replaced, the old concrete forming an enormous pile in the paddock.

I’m writing this down rather than doing something about the disaster outside the window because it’s early morning and this is what I am trying to do in the early morning. Keep my body in a chair. Chase down some words. Most days it seems much less important than doing the work outside, but morning seems to be the only time of day I can write. I’ve always been a lark, not an owl, partly because I’m a terrible sleeper and morning comes as a relief from the endless torture of being in and out of obsessional thoughts and weird dreams. But being a farmer and a writer is like having two buses to catch at the same time. They are both going places you want to go, and you have to choose. The farm bus has a much louder horn in spring and summer so I abandon this morning writing thing for many months. I’m trying to catch the writing bus again, now, if I can remember how.

When I start writing again in fall, the farm’s To Do List still makes an appearance, like a hungry hound at the study door looking for breakfast. No, I say, Stay. You have to wait. But its presence lurks and bothers me, as do my very cold feet under this desk. I didn’t light the woodstove because I would have had to go out for wood and would have been pulled away from writing by the sheep flock wanting hay and the bin of carrots needing washing and the part of the wood pile not stacked. Distraction lurks in every corner of the farm.

The question is, farmer or not, when is one ever not distracted? The morning-effect—getting up before dawn to write, say, and ideally before anyone else in the household, including animals, cares to right themselves —has been explained as the time of day when the brain is associative and malleable. I’m not that creative when I’m half asleep, but I enjoy that my Critic is also half asleep and less inclined to sabotage what I’m doing before dawn. Critics are day-time creatures and are fed by things like emails – the ones you get and the ones you hoped for but may never get - and social media most of all (looking at it once a month feels like enough). My advice is, whenever you write, find a time and place that The Critic, and its side-kick, Self-Doubt, don’t enjoy. Maybe its on a noisy subway, or after a cold swim or when you’re half-asleep in your pajamas at midnight or dawn. Maybe it’s in a busy café for exactly one hour before you have to catch a train.

My Critic is generally not interested in looking out on a snowy lawn at 5 am with very cold feet. (If I were to have to contend with the Critic or the To Do List, I’d take the List every time. It’s distracting but its not a Destroying Angel.) So, my one rule is that I get up and allow myself to type and look out the window, but absolutely no email, phone, conversation or breakfast until I stop. (I do pee, about three times an hour, followed by more tea. These provide welcome stretch breaks and I do in a kind of trance.)

The small farm pond I can see from my office window contributes to this trance – all the light playing on the water as the sun rises, the wavy reflection of trees, visitations from ancestors in the form of birds. It fills me with gratitude and also the sense that life is ephemeral (which can be a source of peace or panic, depending on the day).

This water that is cupped here in a fold of earth for a time is always coming and going from somewhere, like the clouds that pass over its surface. Right now the breath rising up from the river valley is shrouding the pond in fog. As I bear witness to this change over the water I am conscious of how words are also like water, appearing and disappearing, making new forms, never fixed for long. We shouldn’t be so attached to them, really.

I discovered this past year that I deeply believe in writing routines, even as I struggle to keep them, even as I believe in the slippery power of words and thoughts and in the impermanence of all states of being. I refrain from defining myself as a writer or a farmer, though I spend all my time doing both. What I am being is undefined from one moment to the next. And perhaps because of this existential swirl I naturally inhabit, routines and structures have always eluded me. All my life I have tried to keep to a schedule or plan and utterly failed (much to my partner’s despair). But one of the wonderful things about getting older is you begin to know yourself and stop trying to make yourself be what you are not. It frees up a lot of time and mental space for other things.

So, without ever making it a hard rule, I have learned how stumbling here to my desk every morning to type calibrates my inner compass. I keep doing it only for that reason. I wrote The Salt Stones over two winters, and without that morning routine it never would have happened. I finished the manuscript in May, and this summer spent time with it only to go through the copy editor’s marks, with strict instructions from my editor not to add or change too much. (The task reminded me of weeding baby carrots: careful work, not to disturb what was planted.)

The minute I turned in my manuscript this spring, the farm bus honked loudly at my door. I desperately needed my early morning hours aside to get out and tend to the lambs and gardens, but for the first time, I felt unhinged. Sitting down with my thoughts and words had become a touchstone and a practice absolutely fundamental to my well being, even though at the time it had felt like a difficult and even foolhardy discipline to carve out.

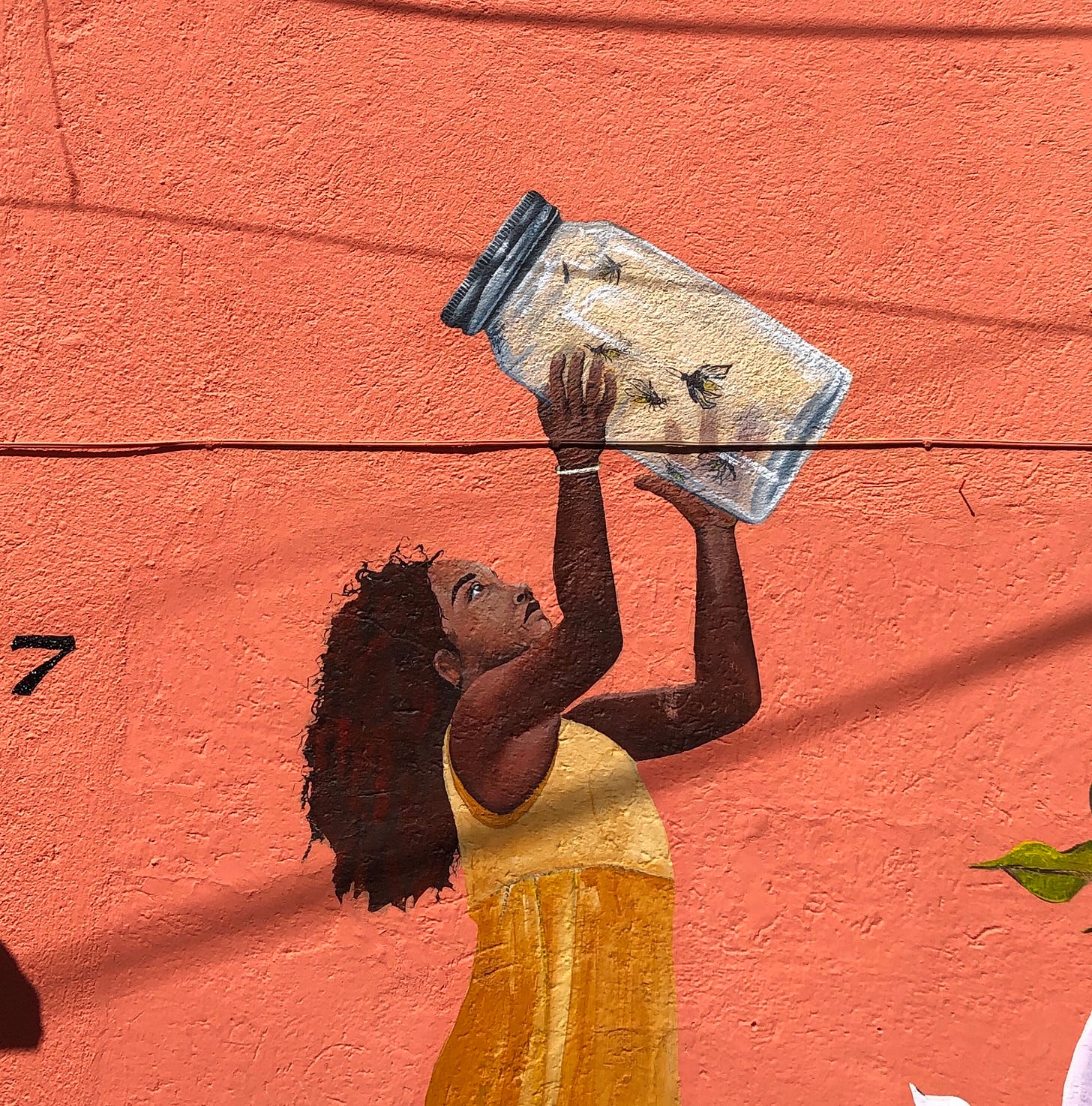

Three weeks ago, Peter and I drove a few hours away to join a Brazilian couple sharing the ritual of Ayahuasca. We were invited by a friend in their community, and Peter had been once before and wanted me to experience it with him. I was a little scared.

We arrived in early afternoon and settled into a ceremonial space with about thirty other people. Everyone sat in a broad circle on mats or cozy pillows they had brought, along with journals and sacred objects. The guides were dressed in flowing white cotton and wandered among us, hugging, welcoming, all in hushed anticipation, reminding me of people watching an eclipse. One of the guides, who is also a sound healer, arranged over a dozen musical instruments. He would miraculously play and sing and envelop us in sound continuously for the next six hours.

In my notebook, already a bit woozy and just before the medicine obliterated me, I scratched out -

We all drank the same infusion of the same plant, and yet we had wildly different journeys. Some people were singing and dancing, while others were weeping and retching, and others stayed cocooned in blankets, covered in tears. As we returned, many hours later at dusk, it was as if we were seeing each other’s faces for the first time with a kind of wonder. There was a closeness and openness among the group that hadn’t existed before.

The medicine was medicine because it was doing the opposite of asking us to be the same, to look or feel the same, to be healed the same way. It was accessing our most individual authentic selves, an imaginal realm that exists because of our particular make up and experiences. And yet we think there’s a recipe to being good or right, to success and happiness, even to physical and mental health. This righteous idea, which seems unique to humankind, has created untold misery in the world. The plant medicine does its healing by showing you what you already hold within you but society deemed unworthy and helped you unsee.

I believe writing can do that too.

Around the fire, as we were all coming back from our faraway journeys, our guide, in her beautiful Brazilian accent, was talking about how she works with the medicine. “With the journey, to see what the medicine wants to reveal to us, we must stay aligned and awake, not thrown by our visions and emotions but able to observe them. The medicine is to reveal our humanity,” she said. “What is it to be human? To have humility, to have compassion, to have insight.”

As I listened to her I realized that these – humility, compassion, insight – are the ultimate goals of my writing as well. To witness what’s most real for me and to try to put it down. To find my way there, word by word—practicing, starting over, watching, witnessing, changing. I write best when it’s not for anyone else; it’s for understanding something. It’s for capturing a play of light or a shift in perception that, when it has gone again, I will hopefully be made more whole, more humble and more compassionate for having stopped long enough to see.

I would love to hear why you write. And how you write, where and when. How do you keep your destroying angels from the door? What helps you write from an authentic place? Do you struggle with not writing as much as with writing?

How can we help each other?

Sending love and loving muses your way –

H.

Why do I write? It’s sort of a scary question for me, Helen, in part because I haven’t quite figured out why I write. I write about nature — an imperfect word for what’s most genuine in the world: whatever walks, hops, swims, slithers, flies, grows, or sits there evolving or decaying (or both). Anyway, I think that my bond with nature makes me a better human being. And I suspect that I write not really to say anything about myself (honest), but more so to share with others the experience and opportunities in the natural world. I do write for me as well, however. At ease and at home among wildlife in wild places, I write to help me find my footing in the rest of the world, maybe make some sense of the place ... and the humans who've messed things up so terribly.

But I shall continue to think (maybe even write) on this. Thanks, Helen!

“I am conscious of how words are also like water, appearing and disappearing, making new forms, never fixed for long. We shouldn’t be so attached to them, really.” This might very well help me get to my desk today, Helen. Thank you. It takes aim at my own committee that wants to make sure whatever words come out are ‘right’ but generally just prevents any words at all. This all so true and beautiful. Thank you.