Dearest Readers,

I flew out to LA this week, just after an atmospheric river dropped eleven inches of rain on California. We crossed the cement gutter that is the Los Angeles River on the drive from the airport. I'd never seen any water in it before; in the city at least, the damage was invisible, pollutants cruising out to wreak havoc in the sea.

My father has been marooned in this city since he started radiation for metastatic bone cancer a year ago. He's 85, and for the last 25 years was a doctor at UCLA, so when his retirement and illness coincided just before the pandemic, he wanted to stay with the team of oncologists he trusted, rather than move to New England to be with us. He lives in a small apartment full of books on the eleventh floor, overlooking an endless pulse of cars on a six-lane avenue. If I tune out my ears in just the right way, traffic on wet tar can sound like the sea. Except when the sirens go by, or a big truck, or the roads are dry, which is most of the time.

Dad is a little better than when I saw him in December when he was in the hospital for loss of blood. He's very thin, has lost the rest of his hair and eyebrows, and straps his left arm across his chest so that he won't jar a broken rib that sticks out just below his shoulder blade. His femur - last summer - and now his ribs are slowly eroding, but there' s a limit to the surgeries that can pin them together. He ditched the last rounds of chemo because it made him feel like he was ready to die, so for now his mood has lifted again; he's reading and listening to music. He says he wants me to help him "sort some things," which is a good sign that his temperament for tidiness and order is intact.

Yesterday, he read the New York Review of Books, then clipped the corner off with a pair of scissors and put it neatly back in the stack of magazines on the bench in the kitchen. He filled the antique ceramic ginger jar that has sat by his reading chair forever. (When I was little, in our farmhouse in New Hampshire, I would sneak pieces of the sugary peppery treats when he wasn't looking.) He jotted down a few bill-related things in his loopy handwriting in different colored inks in a system known only to him, and he fell asleep for a while in his chair. We ate soup sitting in bed and watching the news and we refrained from saying all the usual depressing things about our democracy.

Instead, news getting repetitive, we got to talking about the idea of "the good life." Dad recommended a book by Sarah Bakewell, How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer. He felt some of Montaigne's preoccupations were similar to my own, I think. And to his. Although my father has spent all my adult life in cities being a doctor, his own books (A Mood Apart, American Mania, The Well-Tuned Brain) are concerned with emotional well being and society. Pretty much anything we do will lead down the same path to this conversation, how to live a meaningful life.

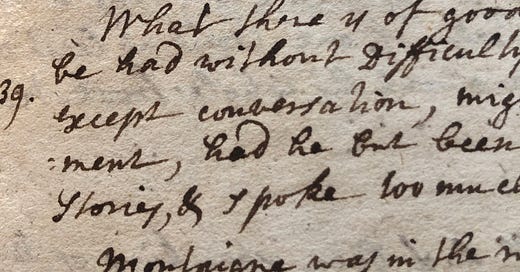

As I was flipping through How to Live, Dad went to a high shelf and pulled down a mottled leather bound book that rumbled as he cracked it open. The first pages were filled with the most beautiful sepia cursive written with a quill pen - annotations written by an early owner of this volume of Montaigne's essays, a third edition, published in 1632. One annotation reads: "What there is of good in Montaigne's Book is not to be had without difficulty. What there is of ill, I mean except conversation, might have been corrected in an moment, had he but been warned, that he wrote too many Stories, & spoke too much of himself."

As most reading this will know, Montaigne is said to have invented the personal essay, even pinpointing the word, essai, "to try," and was putting his thoughts and experiences on the page when no one else was doing so. "He fell off his horse and had a meeting with death," explains my father, "and thought he had better start writing it all down." (These days, our conversations often chart a course toward how to face death, of which Montaigne also had plenty to say.)

Bakewell writes, "[Montaigne] may never have planned to create a one-man literary revolution, but in retrospect he knew what he had done. 'It is the only book in the world of its kind,' he wrote, 'a book with a wild and eccentric plan.' Or, as more often seemed the case, with no plan at all. The Essays was not written in neat order, from beginning to end. It grew by slow encrustation, like a coral reef, from 1572 to 1592. The only thing that eventually stopped it was Montaigne's death.....Looked at another way, it never stopped at all. It continue to grow, not through endless writing but through endless reading."

As a case in point, the person who annotated this ancient volume I have in my hand, a critic of Montaigne at first, closes his handwritten pages of annotations thus: "He that talks frankly of himself is perhaps no more to be blamed than he that never talks of himself...and I dare engage he will be read to the End of the World."

I myself owe a debt to Montaigne as I essai first-person nonfiction in The Salt Stones. And I owe so much of my love of books to my father, whose phrases often arise in my head as I write, to say nothing of the craving for ginger. I hope, this summer, to sit in the peaceful green fields of Vermont with him, but for now, here we are. And we have books and each other.

Helen

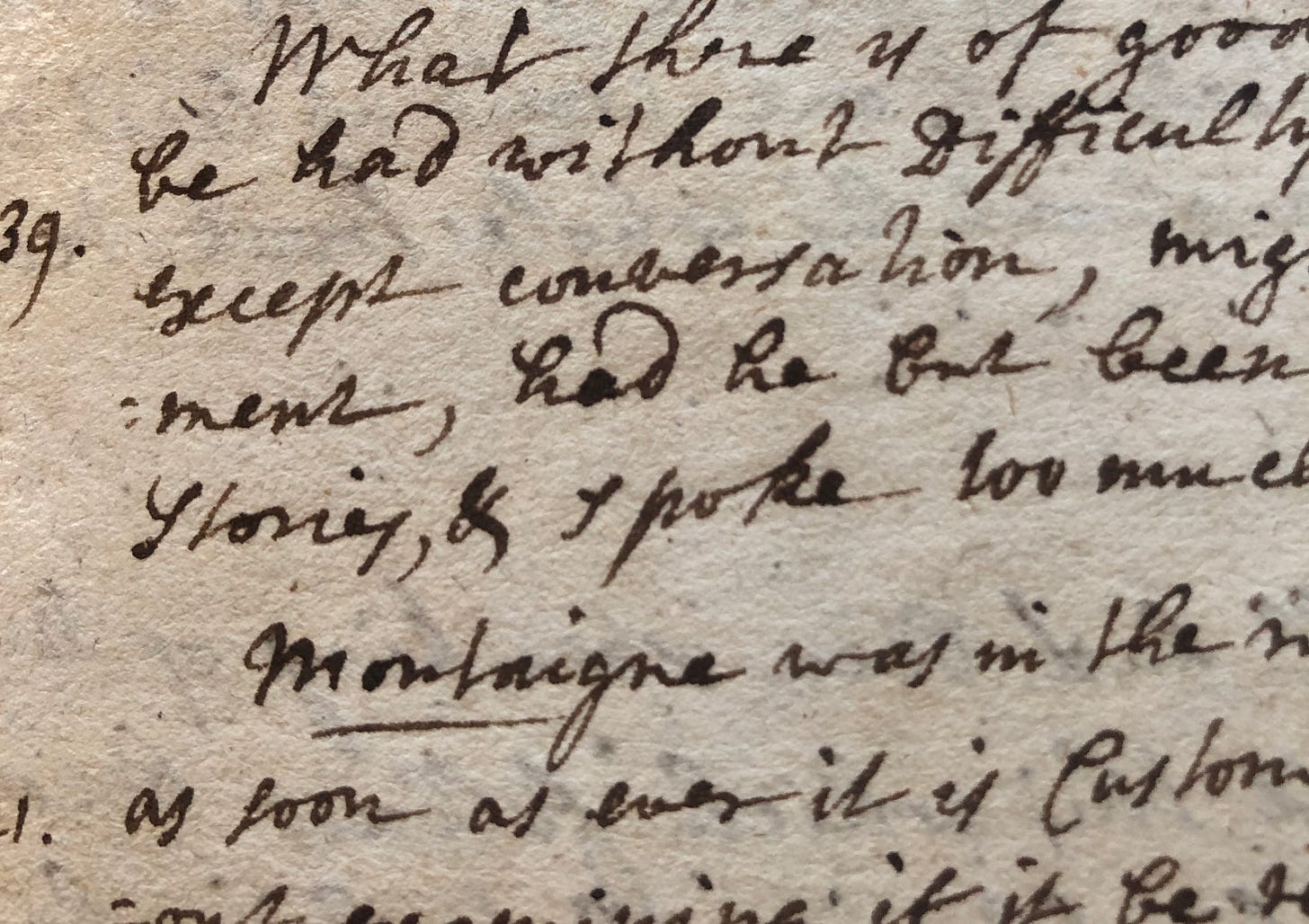

A photo I took of my father, years ago, writing American Mania.

P.S. If you enjoy these posts, I hope you’ll write and we’ll stay in conversation. I still don’t fully understand how to use Substack, and I worry that it’s annoying all my friends with unnecessary bobs and buttons. Everything I write here will remain free. Please support my writing if you’re so moved, but feel no pressure. I am delighted to share my thoughts, and if one day I finish The Salt Stones and you buy copies for all your friends because you love it, that will be my greatest unimaginable reward. Thank you!

"No pleasure has any savour for me without communication. Not even a merry thought comes to my mind without my being vexed at having produced it alone without anyone to offer it to." —Michel de Montaigne (1533-92)

Thank you for this lovely post! It reminds me of the days when my father was elderly.

If you or your father need a respite within LA, the guesthouse at Pepperdine U is very peaceful. It has a good view of the ocean, and one can wander about the famous easily. The photo reminds me of the cafe at paradise cove before the new renovations.

I love your writing about your father. I'm also writing about my relationship with my 96-year-old father. That photo is gorgeous. It says so much. May your time together be wonderful.