My mother is sleeping on the dock by the pond. She's sleeping very soundly, curled like a cat on the edge furthest out over the water, in dappled shade. Every once in a while - I can view best through the small pair of binoculars on my desk - she rolls sideways, stretches out a leg and preens herself with a quick stroke of her head. When she first arrived, she took a swim, splashed her face in the water and threw some bright beads over her back, lingered for a while in the reeds by the edge.

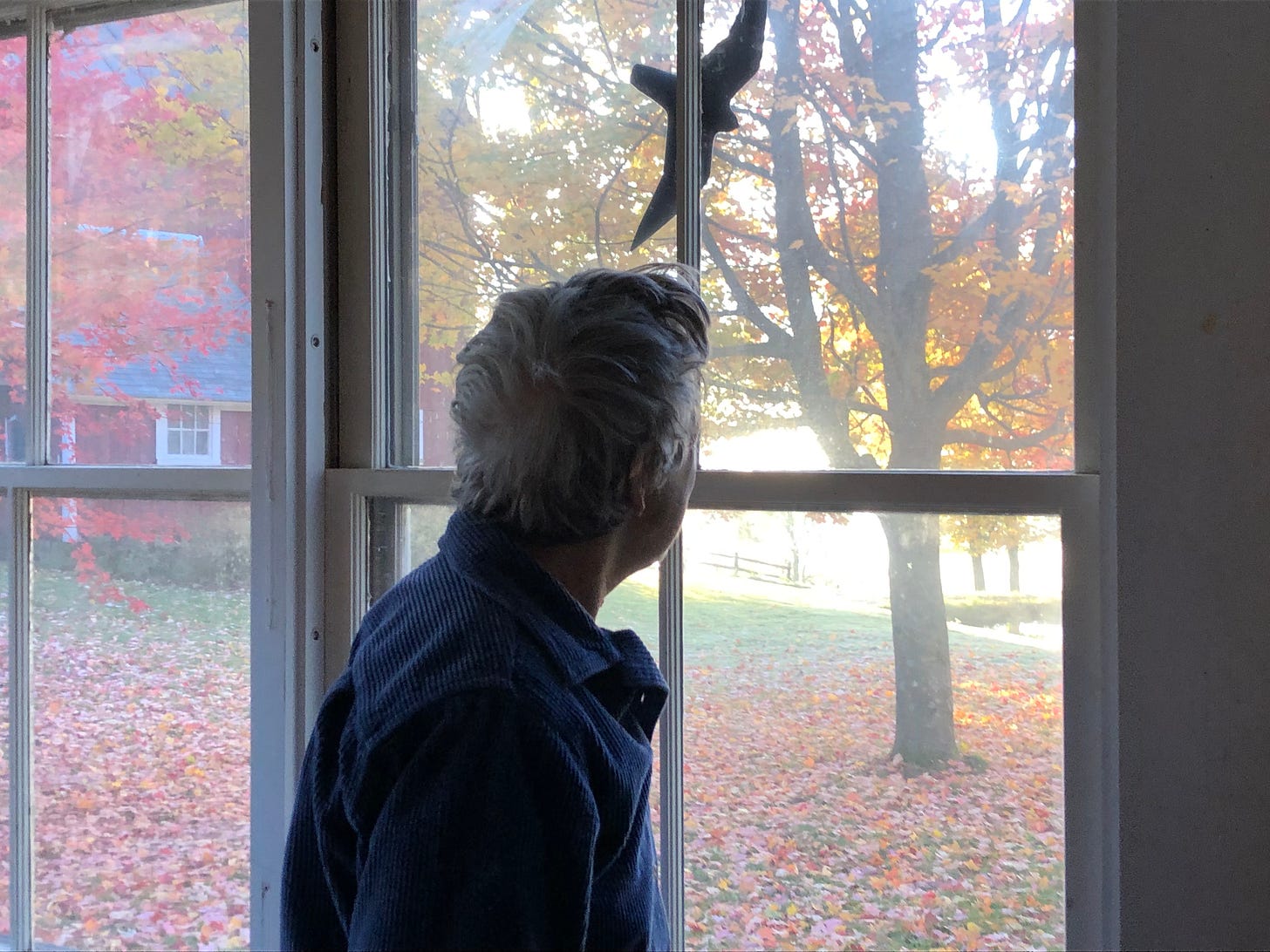

The feeling I had as I watched her was of contentment, even joy, and of being at peace in this gorgeous morning light of early autumn, amber and slanted and full of poetry. And now, she sleeps. She seems so very tired, as if she has gone through a mighty battle and a long journey, as if she has passed over storms and seen the heavens. Which she has. She is gone, my mother, and her spirit is returning in new forms, today and yesterday in the body of this mother mallard who rests in my garden. I recognized her immediately, as one does with someone you have loved so long. Her spirit is finding ways to give my heart solace.

This rest, and this pleasure in the small things in life—a swim in cool water, golden morning light, a nap in the grass and a stretch of strong limbs—was long denied for my mother, who died a few days ago in a care home for people with Alzheimer's dementia. This is especially tragic because my mother was a person who was not only most at home outdoors, but who adored the small pleasures of life— and shared them, reveled in them, made them magic. Her cup was not only half-full, it overflowed, and it filled other people's cups as well.

This relentless illness took away everything, bit by bit: her ability to walk, to read, to have conversation, to find purpose, to find meaning, to recognize her family. What mercifully and miraculously remained was her ability to give out love and appreciation to the nurses who took care of her and to anyone who visited. She still smiled her brilliant smile. Her last coherent words to me were "thank you," which was so like her. I was washing her closed eyes with a warm washcloth, and stroking her hair. She had been in pain, but that day she looked peaceful. She turned her face toward me, eyes still closed, and gestured for me. "Forehead," she whispered. "Thank you," she said every so softly as I passed the warm cloth over her brow.

I miss her so much. I've been missing her for years. The minute she died I felt a profound exhaustion, and a loosening of the guy ropes that had kept me tethered and standing strong. I hadn't expected this. I had years to prepare for this grief. I had her company in my imagination as I wrote my book about shepherding, The Salt Stones, where she became an important figure linking my sense of belonging, love of land, memory and meaning. As much as it is a book about being a shepherd, it's also story about mothers and daughters, and about the small things in life that are ultimately, at the end, the most profound. This belief in small things is one of the many gifts my mother gave me, and in hard times is what keeps me going. Notice the light. Notice the birds. Notice this bird.

Here's a passage I wrote about her in The Salt Stones (to be published in spring 2025), after visiting her in her care home 2 years ago:

I park the truck, walk to the lobby and hit the buzzer, put on a mask. The pandemic has mostly passed, but the young man at the front desk still needs to check my temperature by holding a small plastic gun to my forehead before letting me walk up to my mother’s room on the second floor.

A nurse is giving her a shower. Mum is sitting naked on a stool in the shower stall, and the nurse, Dee, is standing just outside the curtain, spraying water with a handheld nozzle and rubbing Mum’s back. Mum’s body is as small as it ever was, her tummy flat, her breasts folded down like pockets in a coat. Her skin is mottled with brown spots but is surprisingly firm-looking, not hanging in lacy drapes as one might expect at age eighty-four.

Her lower legs and feet, though, are deep purple. Her capillaries spill beneath the skin like dark-red ink on old parchment.

Mum looks up when she hears my voice, peers through the water, sleep grains caught in her lashes, hair plastered to her head. She squints, distant, uncomprehending, her smile more of a question than an answer.

Another nurse comes into the small bathroom, and together the two women gently but firmly convince Mum to let them lift her weight off the stool, turn ever so slightly, and sit down again in a wheelchair. She is terrified to stand, sucks her breath in, clutches hard to the shower rail and won’t let go until, finally, I have to pry her hand away.

Instructions like “Let go with your hand,” or “Step back with your foot,” no longer compute; her brain cannot make sense of that in physical space. So any moving we do scares her—it is all a surprise and a potential toppling.

She has lost words, and with them the ability to walk.

Dee wheels Mum into her bedroom, and I put Mum’s pajamas on. I give her a very long hug, her wet head against my belly.

“I love you, Mum. I’m sorry I haven’t been here in a while, but I didn’t want to give you my cold. You know I’m your daughter, right? I’m Helen. I love you so much.”

Often if she doesn’t remember me, I will show her photos of the farm and of the lambs, especially one photo of a few years ago when she could still get out to the barn. She’s sitting on the steps with Chance and Lightning climbing on her, and she holds a pink baby bottle, her face beaming. The lambs always trigger her memory of who I am and where I live.

She looks at me again, and suddenly, for a moment, she is all there—her utterly loving and present regard.

“Yes, darling. My Heli. And I love you,” she says.

In that moment I feel her entwining, her regard like a strong tendril, holding me up. I feel Wren in that moment too, and the tenacious vine that grows and holds us all—mother, daughter, mother, daughter—even as the ground crumbles beneath us, as we lose time and space and words and even each other.

The belief in small things is one of the many gifts my mother gave me, and in hard times, is what keeps me going. Notice the light. Notice the birds. Notice this bird.

All morning the mother mallard sleeps on the dock, and she is still sleeping in mid afternoon when a large family comes to walk around. Our farm is open to the public, and it is normal to have folks we don't know exploring the grounds and crossing the lawn. They head toward the pond; there are green frogs there, and dragonflies resting in the fringe of orange jewelweed around the edge. I almost run out to stop them, to tell them that a spirit is taking a rest, but they are well ahead of me. The children run straight for the dock and I see the duck fly up, bank her wings into a steep curve, and beat rapidly over the field. My heart cries out for her to stay. But she looks strong. She has places to go.

In what forms do your departed loved ones visit you? Does this bring you solace? In what moments are they the most present, palbable and speaking to you? Do you believe, as I do, that birds cross the boundary between heaven and earth and have messages to bring, when we stop to receive them?

I'm sorry I haven't written for so very long. Writing is so healing, especially when it becomes a conversation as it can here, but often it is hard to begin, hard to find and believe in one's words. That's the space I have been in this summer and am trying hard to fly out of. Once again, my mother has given me what I needed to hear, as she always did. Rest. Rest some more. Then simply take flight. Everything's gonna be all right.

.

My mom is in her own period of decline. Loving her as well as she deserves to be loved has always been hard for me and I'm moved by the tender description of your care for your mom. It's a nice reminder to me to work hard to find those moments of connection and compassion, in the hopes the peaceful birds will come to visit me when that time comes.

Faith in little things — sending you and the family love and warmth, Helen.