photo by Dylan Ladds

In a quiet moment on Thanksgiving morning, made quiet in my mind because the sheep were happy with their pumpkin and strewn hay, I sat by a fire, opened Madness, Rack and Honey, and read this line in an essay by Mary Ruefle:

People, the people we really love, where did they come from? What did we do to deserve them?

The essay I was reading was about secrets, and I do not know why or from where in the author’s secret poetic mind these lines spilled out, except that they also speak of some great mystery. How do we explain, or touch, the loves we carry in our hearts? I carried these lines with me all day.

There was a winter storm brewing. It snowed and snowed. At first it seemed to melt out of the air, but by noon it began to blanket the ground. Willow was taking a bus from Boston with her boyfriend and two friends, then driving a borrowed car the rest of the way to the farm. In a last minute aborted rescue, at dusk on our very steep, unplowed and icy hill – they couldn’t make it up – Wren and I ended up abandoning two more cars off the road at the bottom, with no way to get back up but walk. The drive down was terrifying, but the walk up was lovely.

Our dear friends Rani and Scott and Quinn planned to drive from Connecticut, but wisely postponed until the next day. Zoe was coming, and Luke; and Cathi and Rick, who had been with Cathi’s mother who had lost power at her house; and Jed, after working all day on the mountain, and Gavin, my nephew. It was a day full of anticipation of seeing people we love, of worry that they would be safe on the road. A day of chopping garlic and herbs to rub with smoked salt on legs of lamb, a day of preparing vegetables from the root cellar, of setting a long table.

It was a day of snow clinging to every twig in a tight, ephemeral embrace.

photo by helen whybrow

In the afternoon I walked up the hill above the farm and thought, what did any of us do to deserve such beauty? This welling up, this overflow of love for all my people gushed onto the hillside and the trees, the quiet fields and the flock of sheep nuzzling the frozen tufts of grass, the owl that slanted across my peripheral vision to a bare branch and huddled there as the snow came softly down.

I imagined a long table set in the white woods, extravagantly decorated, heaped with all the food that comes from the land – seed and suet, leaf and root, flower and fruit – and little by little it being consumed by the creatures who came upon it, right down to the table itself becoming food for fungi and insects.

I walked to the Memorial Forest, a place in the woods where we have dedicated little wooden structures to the memory of loved ones who have gone but remain alive within us through their stories and influence. The structures are decorated with photos and notes, a beloved sweater or handmade spoon, fragments of memory and story, of love. It used to bother me that the mice ate everything we left behind, turning photographs to colorful confetti, but Peter reminded me that it doesn’t matter. It’s that we left it there that matters, not the thing itself.

photos by helen whybrow

Mary Ruefle writes about beauty in this same vein, that it is not the thing itself that’s beautiful but our moment of noticing:

“You think the rose is beautiful and so you may also think with sadness, that it will die. But the rose is not the beauty. What beauty is is your ability to apprehend it. The ability to apprehend beauty is the human spirit and that is what all such moments are about….”

The ability to apprehend. I write about this in The Salt Stones, about how the act of noticing and listening is the doorway to caring for the land and the flock. And perhaps for everything. Apprehend is a great word, like a composite of appear and comprehend. To be stopped in our tracks by something we recognize as real.

photo by helen whybrow

Mary again: “What you carried with you when you walked through the door was this ability. It is your ability to apprehend beauty, or the lack of it. It is your ability to listen. And change, or be changed.”

Gratitude, like beauty, requires stopping in your tracks. I think the magic of gratitude, and of the offering of gratitude—the Thanksgiving table, the note in the woods for a loved one who will never read it, a candle you light, a feeling you carry—is that it can’t be measured. There is no such thing as enough, or not enough. Any genuine offering you share with intention represents all you have been given and all you have to give. The gods have always understood this. That you make this ritual gesture of givingness is what matters. The ritual gesture makes the fragment whole.

I don’t always remember this. I want to.

I want to learn to live well with the pieces I have.

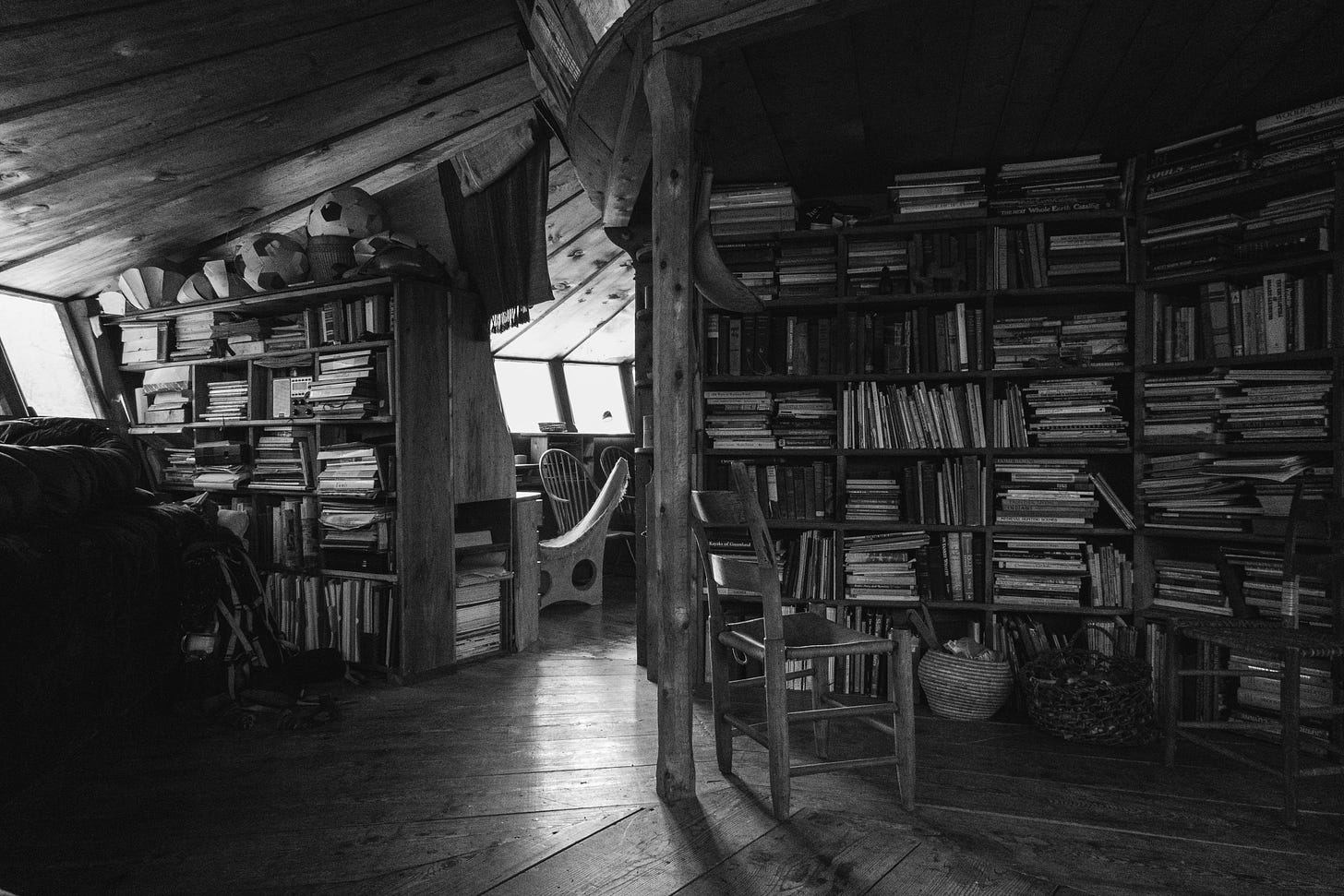

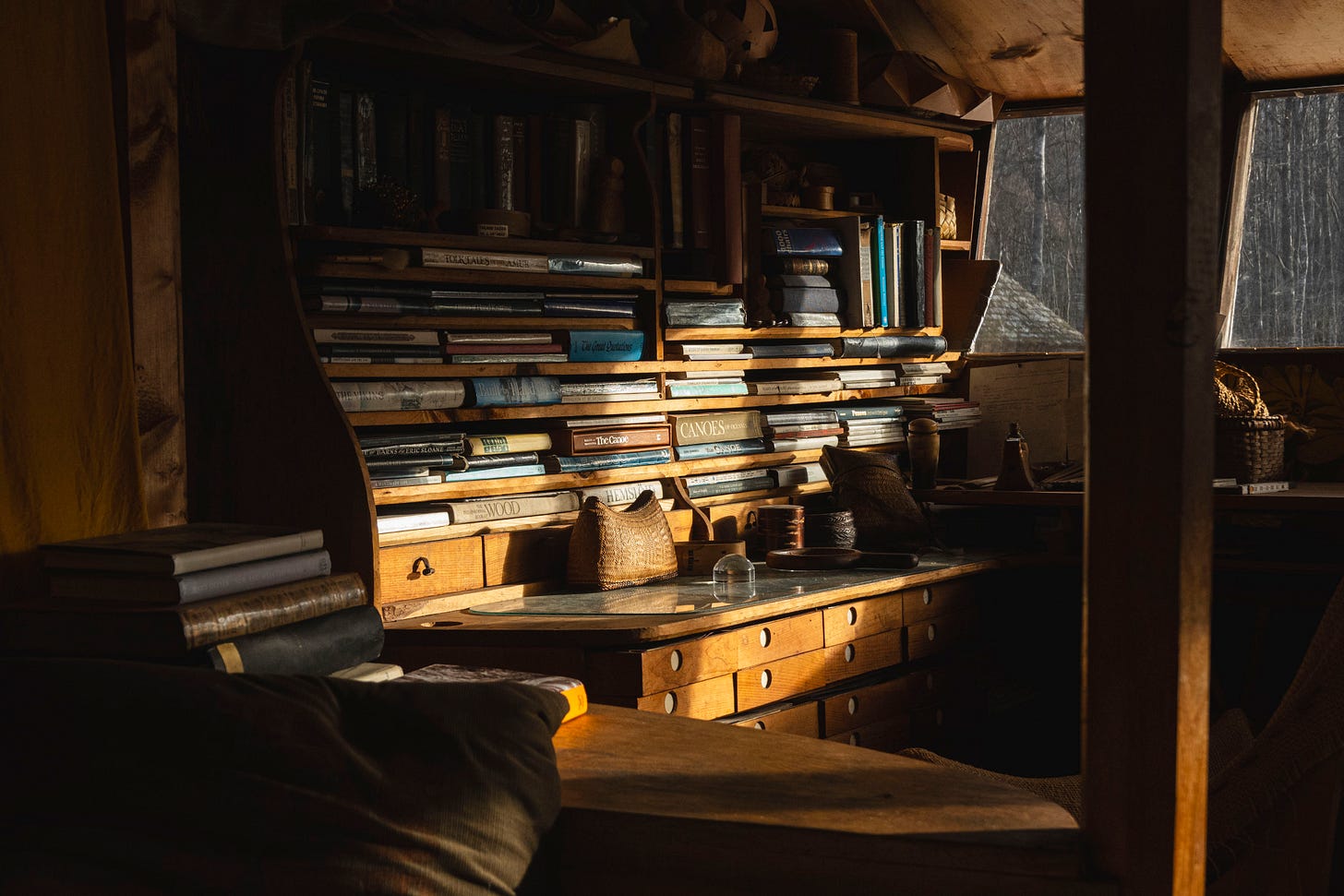

photo by Dylan Ladds

A Winter Reading List

Because it so often happens that my writing starts from reading something that apprehends my imagination, I wanted to share some books I’m enjoying, plus a handful of others I want to check out this winter. In my current pile, I seem to have a few themes going at once, which tracks with my easily distracted state of mind these days, but also makes it easy for me to continue reading whatever book suits my mood and my number of active brain cells at that moment.

I read mostly nonfiction, but novels are dearest to my heart in winter months, when nothing else comes closer to dispelling the dark.

Two powerful, intelligent books that are changing the way I think about so many things are: Undrowned by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe. These are very different books but share themes of Black Liberation, imagination, and a deep reckoning with colonialism and the reality of life for BIPOC people in the “afterlife of slavery.” Gumbs’ project is generous and nurturing while also fierce, concerned primarily with finding and sharing liberation within oppressive environments, which she calls “unbreathable spaces.” (“I do not commit to playing a permanent role in a structure designed for our infinite lack,” she writes.) Sharpe raises more pointed questions about how truth and reconciliation is handled and who it serves. She also writes about beauty as a method of resistance, an idea I find radical and want to think more about.

I’m incredibly excited to read Gumbs’ biography of Audre Lorde, Survival is a Promise.

On a different theme, I’m learning about agroforestry and silvopasture as part of my ongoing research into pastoral traditions that we might want to bring back as ways of making small-scale farming more viable, ecologically healthful and just more joyful. Big trees in pastures for shade and cooling as the climate blazes, sheep feeding on coppiced willows and fertilizing apple orchards – these are images that I find super hopeful. Two books that take a broad approach to designing farms around a pattern language of animals in the landscape, building complexity and working with nature, are Call of the Reed Warbler by Charles Massy and Nourishment by Fred Provenza.

My father recently sent me Shaping the Wild by David Elias, a shepherd and conservationist who writes about wild-farming his hillside in Wales, so I’ll check that out next.

photo by Dylan Ladds

Ah, and now fiction! My book designer, Mary Austin Speaker, who created the beautiful jacket for The Salt Stones using Wren’s block print of the farm, turned me onto the exquisite novellas of Claire Keegan. Mary said I should check out their cover designs, which are also block prints, but open those gorgeous covers and you will not close them again until you have read every word of Foster, or Small Things Like These or So Late in the Day. This Thanksgiving holiday was a Claire Keegan book-a-thon in our house.

Finally, Jean Giono, my mythic companion, my muse! I want to check out the novella Fragments of a Paradise, just translated by Paul Eprile. He, like me, discovered Jean Giono when he picked up a book in a book store, read the back cover, and was immediately swept into a great love affair with Giono’s language. Fragments is a book that Giono wrote while under the Nazi occupation of France during World War II, and, though I haven’t read it yet, I recently read his Occupation Journals (translated by Jody Gladding). It feels potent to read such works at this time of wars and to contemplate this great writer’s struggle to make art that also attempts to make sense of the brutality of the world around him.

Can any sense of this mad world be made, then or now? Giono resisted resolution. So did T.S. Eliot, writing entre deux guerres.

“Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure…”

So. That’s it for now, my friends. Sending love and comfort in these days ahead.